Cleaning Up Our Rivers

Farmers as Partners, Not Scapegoats

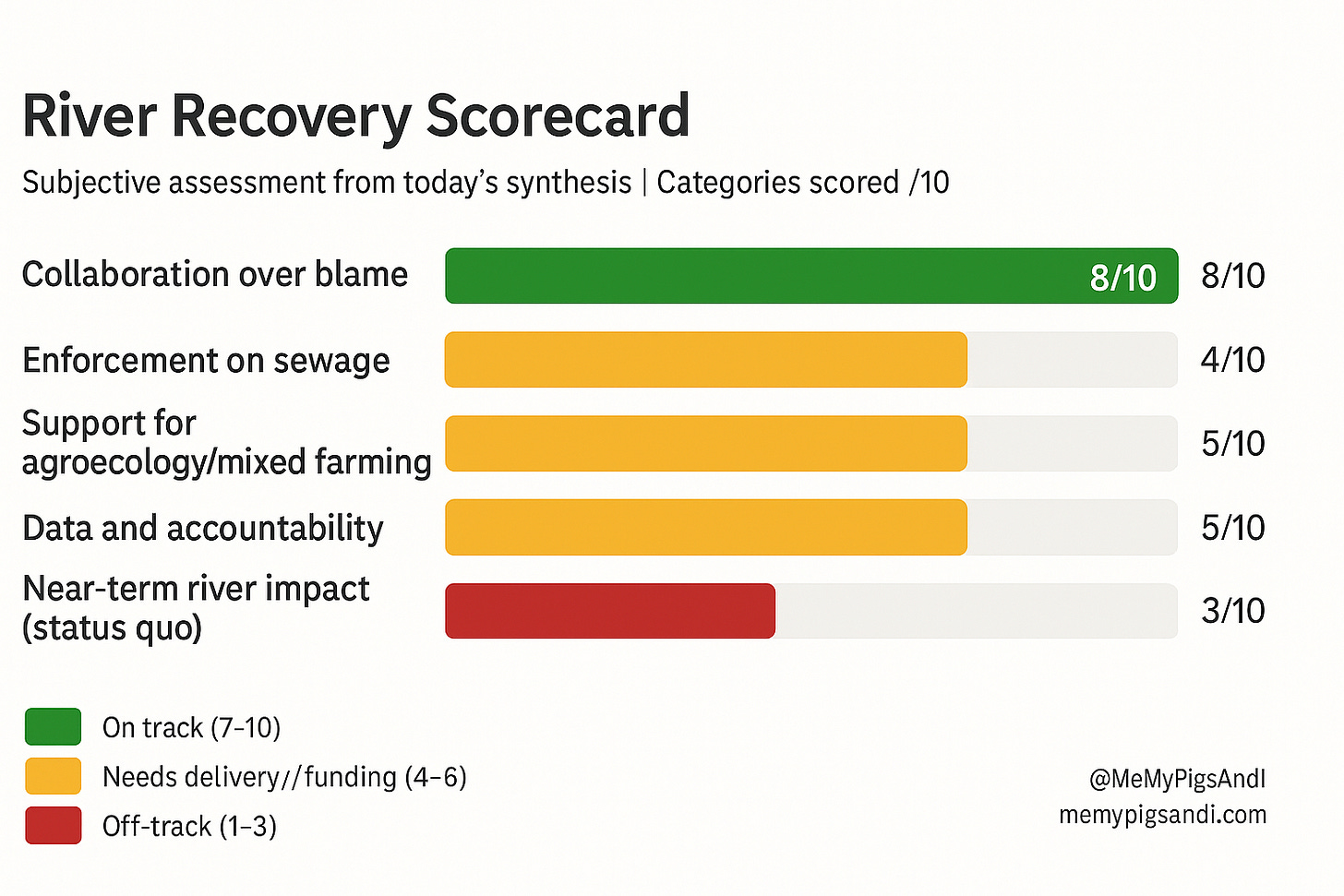

UK river pollution is not the fault of “farmers” as a single group. It is the result of a system that tolerates sewage spills, rewards chemical‑intensive production, and concentrates livestock in factory‑style units. The Nature Friendly Farming Network calls for collaboration over blame. The Sustainable Food Trust sets out how well‑managed livestock and mixed systems can help rivers recover. Parliament’s EFRA report exposes persistent accountability gaps. The task is practical and shared: fund agroecology and catchment‑scale action, enforce against all polluters, and reward farming systems that keep nutrients in soil rather than in rivers.

Flooded Fields, Failing Systems

If you work the land, you have felt the change. Winters now sit heavy and wet over fields. Summers swing to heat and hard ground. In a year like that, soils either hold the line or they give way. When soils fail, water takes the fastest path downhill and carries phosphorus, nitrate, and sediment with it. This story is not only about farms. It is also about sewage infrastructure that spills when it rains and rivers that reflect every weakness upstream.

Politics has caught up with the problem. The EFRA Committee’s Water Quality in Rivers report names what must improve: monitoring, enforcement, and investment. The new DEFRA Minister for Water and Flooding has appeared before the Committee in a session that put these issues on the record. The public wants cleaner rivers. Farmers want a fair shake. Regulators are now on the hook. The real test is whether strategy becomes delivery in every catchment, not just a few pilots.

What NGOs Are Saying

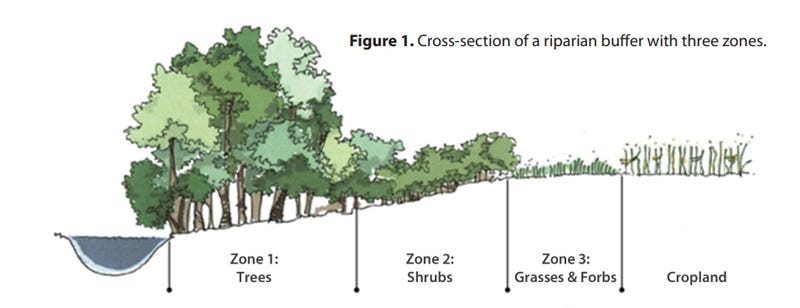

NFFN’s message is practical. Stop blaming farmers as a class and build catchment plans that work. That means buffer strips where they make a difference, soils that do not shed in a storm, and funding that fits the farming calendar and margins. Collaboration beats slogans.

The Sustainable Food Trust makes a simple case. Livestock, when managed well, helps. Grazing that builds structure, longer rotations with deep roots, cover through winter, and manure handled as a nutrient asset keep nutrients on fields and out of rivers. After rain you can see the effect. There is less surface sheen and more water soaking into the ground.

Sustain draws a clear line. Factory farming concentrates animals, creates excess slurry, relies on cheap synthetic inputs, and leaves ground bare or compacted. That model loads risk into the system and shifts costs onto rivers, wildlife, and rural communities. This is not “farming” as a whole. It is a specific industrial approach.

What Parliament Identifies The EFRA Committee scrutinises DEFRA and its public bodies. It holds evidence sessions, publishes reports, and seeks Government responses within two months. The river quality report is useful because it names the gaps. There has been underinvestment and weak enforcement on sewage, patchy monitoring, and slow follow‑through. The report also sketches what a functioning regime should look like. Targets must mean something in each catchment. Data should be visible to the public. Penalties should bite. Funding should be aimed at the highest risk places first. Ministerial appearances make accountability visible. The next test is whether budgets and timelines match the promises.

How This Lands on Real Farms

Last winter did not arrive as weather. It arrived as water. In parts of England, fields sat under flood for weeks and were hit again when the next system rolled through. Carbon Brief’s analysis shows English farmers received record flood relief after last winter’s rain because so many were pushed beyond what they could absorb. Relief is the last resort. You apply only when the crop is gone, the tracks are impassable, and the bills are already piling up.

For livestock farmers, floodwater is more than a number on a gauge. It moves with force, it carries debris, and it kills. In Wales, almost 300 sheep died when river banks failed and waves of water swept across grazing land, with more than £100,000 of animals lost in a single event. That is a family’s year erased in an afternoon. The clean‑up continues long after the headlines have gone. There is carcass disposal, disease risk, torn fencing, scoured gateways, and spoiled hay and straw. It is heartbreaking for the sheep that died in panic and for the farmers who were already at their limit.

Arable ground tells a related story. When heavy rain hits bare and compacted soil with little root structure, water runs across the surface and takes soil with it. It leaves deep ruts. Where soil is covered and rooted, the same rain behaves differently. A herbal ley or winter cover holds structure, slows the flow, and gives water time to move down rather than across. Any farmer walking a headland the morning after a storm can read the field. You see where water settled, where it cut a new channel, and where a margin or hedge caught the first load of silt.

Mixed farms sit at the hinge. The timing of slurry applications matters because one week too early on wet ground can turn a nutrient into a pollutant. Rest periods for grass matter because a tight, healthy sward holds together under feet, while a tired pasture breaks and poaches. Stocking rates matter because a field that can carry a mob in July may not carry half that number in February. These are not policy slogans. They are daily decisions made with livestock on the move and a forecast that keeps changing.

Real progress shows up when many small, practical decisions line up across a catchment. Farmers share local flood maps and learn which fields let go first. Grant money, when available, goes into the right places. Buffers are placed on bends that spill. Simple wetlands sit just above the village. Extra slurry storage means applications can wait for a dry window. Advice is tailored. It comes from someone who knows the ground, walks it with you, and helps plan changes over two or three seasons. Progress is not measured by a spreadsheet alone. It is seen in water sampling at the bottom of the sub‑catchment, with less phosphorus, less nitrate, and less sediment after the next big rain.

What Would Make This Real

Set statutory catchment targets for phosphorus, nitrate, and sediment with transparent public dashboards.

Fund the transition with multi‑year grants for riparian buffers, hedgerows, wetlands, and slurry or manure storage, plus advisory support for rotations, covers, and grazing plans.

Enforce sewage rules with penalties that are more expensive than non‑compliance and with clear investment obligations and spill limits.

Align markets with outcomes through method‑of‑production labelling and public procurement that buys from mixed, pasture‑based, agroecological producers.

Put farmers in the room through independent catchment boards that include farmer representatives, ecologists, and citizen oversight to prioritise spend and sequence interventions sensibly.

Why Livestock Done Well Helps, Not Hurts

Walk a permanent pasture after heavy rain and the case is clear. Roots knit the soil. Organic matter holds moisture. Water moves through rather than over. In a mixed rotation, a year or two in herbal ley repairs structure that tight drilling windows and heavy kit can damage. Manure from well‑managed herds goes onto ground that is ready to use it. (Remember not all manure is equal. Manure from an animal fed a soy based diets and pumped with antibiotics is not equal to a pasture grazed animal). Animals deposit nutrients where plants can catch them. The factory model does the opposite. It concentrates animals, turns nutrients into waste, relies on synthetic inputs, and leaves soil bare. If rivers are the test, biology usually wins.

Helen’s Opinion

I have watched winters get wetter and summers hotter & dryer. In those swings, soil tells the truth. Farms that have ploughed and chased yield with chemicals, the land gives way first in the tramlines, then at the margins, and finally into the river. When we fed the soil and kept it covered, the same weather became survivable.

I agree with the Sustainable Food Trust on the practical point that livestock in agroecology systems are part of the solution. I am cautious about the way “Net Zero” is used in policy. Too often it becomes a permission slip. Numbers are cut on paper while imports rise in practice. Welfare and shipping emissions are ignored and this gets called progress. That is a rules‑bending game rather than stewardship.

The real problem I think is factory farming and the chemistry that props it up. Pack animals tight, treat manure as waste, strip fields bare, and pollution follows. That model harms our health, animal welfare, rivers, and the viability of family farms that must compete with its cheap output. We need more localised farming and food systems, more seasonal eating, and pricing that reflects reality. Agroecology is not a slogan. It is how soil stays whole when the rain tests it and how nutrients cycle without poisoning the stream below the hedge.

There is no fix for factory farming. It needs to end. If we want clean rivers and thriving rural communities, we should back the farmers who are already building that future and stop subsidising the system that breaks it.

I spend a lot of time digging into reports, fact‑checking, and translating industry jargon into something real. If this helped you make sense of the noise, consider subscribing as a free subscriber or upgrading to a paid.

Deep dives like this will move behind a paywall soon, but right now you can lock in 20% off forever paid subscriptions.

If a paid plan is not possible, sharing this post also makes a real difference. Every bit of support helps me hold the food system to account.

Sources

Sustainable Food Trust - Why livestock could have a key role in cleaning up our rivers

UK Parliament EFRA Committee - Water quality in rivers (report)

Carbon Brief - English farmers received record flood relief after last winter’s extreme rain

EFRA session with new DEFRA Minister for Water and Flooding (YouTube):

If just 5% of my readers tipped £1/$1 this essay would pay for itself in terms of time spent working on it.

I agree Helen. I seem to remember, during our pilgrimage to Wales (my maternal line) we stayed outside Monmouth at a sheep farm - glamping. Sarah was telling us that some industrial chicken farmers had dumped chicken waste/manure into the river Wye which had basically killed the river ecosystem.

It's worth pointing out that you cannot increase the population by 700-900K per year as a Government Policy and expect a sewerage system that hasn't been expanded to cope. That's not to excuse the action or lack of by the Water Companies, but to add a bit of context.

As to your comments and observations on factory farming, they are spot on. Factory Farming is an ignorant bureaucrat's way of solving a problem.

BTW apologies for not responding to your replies to my other comments, I've been travelling for the last two weeks.